Lessons Learned at Modern Memoirs

Publishing Associate Emma Solis during her last week at Modern Memoirs in September 2024

A Farewell Blog Post by Publishing Associate Emma Solis

When I began working at Modern Memoirs, Inc. as Publishing Associate in May 2023, I had just graduated from Smith College, and my internship with the business the previous summer was my only real work experience. I am so happy that company president Megan St. Marie took a chance on hiring me because I can’t think of a better foundation for launching into my career and life as an adult. One year and four months later, I am unfortunately leaving my position to follow my partner and explore opportunities in New York City. My departure does not negate how grateful I am for the opportunities I had here, nor how much I enjoyed working within such a caring, supportive, and knowledgeable team. In the interest of preserving the valuable lessons I’ve learned, I have decided to enumerate them here. To college students and young adults looking to learn about or join the publishing industry, I hope this short list may provide a good starting point to see what lessons you may take away from an internship or first job with a small publisher like Modern Memoirs, Inc.

1. The devil really is in the details.

A book is a collection of countless details masquerading as a seamless unit, each detail so small and easy to overlook on its own. During my tenure as Publishing Associate, I have witnessed the mix of panic and relief that comes with catching a tiny mistake in the late-stage review process, or, more unfortunately, upon receiving proofs of the printed book. During one project, a client’s last-minute addition of a few extra sentences at the end of the chapter had added an extra page that was now missing a page number. We were able to catch the error and resolve it before printing the bulk run of books. This (thankfully unusual) experience taught me that you really cannot double-check enough times, even after receiving the book, and even if it looks perfect on the outside.

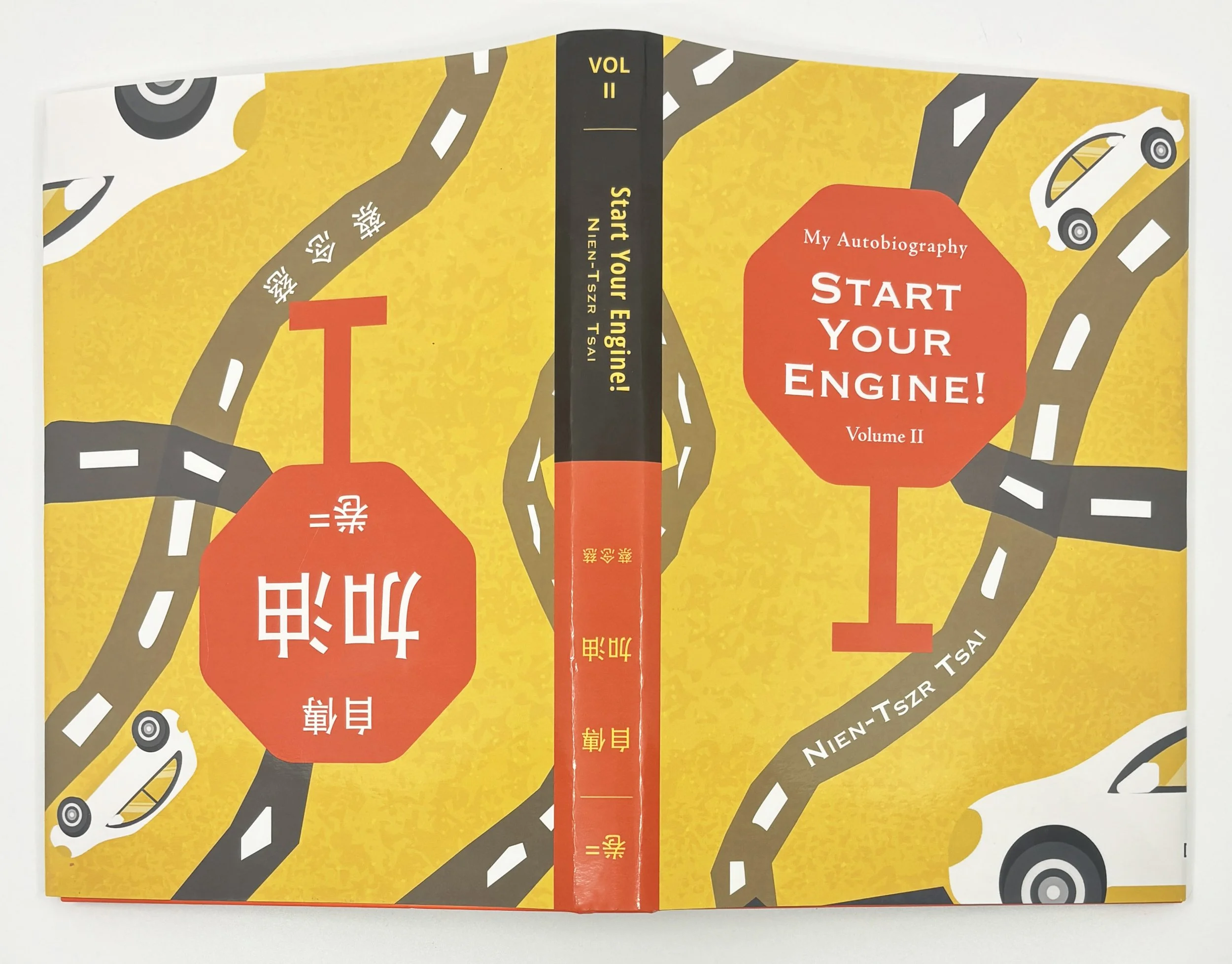

On the flip side, it was often the small details that took a book project from great to superb. These decisions often involved one staff member who had a particular insight into our client and knew how to include a feature that would delight them in the bookmaking process. Including colored endsheets, using a display font that hearkened to the client’s native language, or compiling a list of folksy sayings a client had used in his manuscript—these special touches were a product of the Modern Memoirs staff’s desire to make every book perfect for its particular client. It was deeply satisfying to hear a client’s rave response to details that arose from so much thought and care.

2. Together Everyone Achieves More.

Modern Memoirs’ team truly embodies that acronym you sometimes see on motivational posters: “T.E.A.M: Together Everyone Achieves More.” President Megan St. Marie led our weekly team meetings with humor and warmth, encouraging every member to share their recent progress and struggles, and fostering a supportive, close-knit atmosphere.

Personally, I learned a great deal from every member of our small team. I often worked closely with Director of Publishing Ali de Groot and observed her extraordinary ability to connect deeply with our authors. Because she has written and published a memoir herself, she can offer boundless empathy, patience, and wisdom to our clients; because she is passionate about this work, she imbues it with fun and joy, especially when a client returns to express how much they loved their books!

My design skills have improved tenfold from working with Book Designer Nicole Miller, who brings endless innovation and energy to the Modern Memoirs team. She helped coach me through tricky InDesign features, gave me advice on analytics and marketing, and inspired me to develop a custom Online Author Page product by learning about CSS.

I felt I could always go to Genealogist Liz Sonnenberg for support due to her kind disposition and penchant for offering help. At team meetings, I was always fascinated by her explanations of what she had found in her genealogy research. It was a pleasure to watch her and President Megan St. Marie swap literature recommendations, and to hear about Megan’s latest research and writing projects. In general, the Modern Memoirs team is a deeply creative and passionate bunch, and the energy only grows when everyone is in a room all together.

Creative fields like writing can involve lots of time spent alone, and paths like freelance work don’t offer much outside support. Publishing, however, is a field that relies on constant communication and collaboration—just one reason I was interested in pursuing it! I was surprised and glad to find that much of my role over this year involved being a part of Modern Memoirs’ close-knit team, which appreciates and values the unique strengths of each member.

“I would sometimes come across a line of writing by a client that struck me—maybe the line would be about a recent loss, or connecting with a parent, or just being doubtful about the future—and I’d feel seen and comforted, knowing that someone else at some time had felt the same way.”

3. Everyone deserves to have their story told.

Before beginning my work at Modern Memoirs, I already believed in the value of being able to share one’s story. Writing is a means of connecting with others and broadening our horizons. However, I didn’t expect just how much I would be touched by the stories that came through Modern Memoirs. I found that the outlines of many of the narratives were similar—childhood, school, career, marriage, family—but the details the writer chose to include, and their perspectives, were all unique. I often thought about the writer’s family members and friends, who would treasure the intimate memories, photographs, and records within each book.

Loss is not something we like to dwell on, but it is another common factor of every person’s life story, like childhood and a career. Just a few months after I started at Modern Memoirs, I learned that my dad was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Not having any other family history of cancer, I was shocked and gutted. Fortunately, my dad is still battling his cancer today, and is even able to travel from Texas to visit me. In the months that followed his diagnosis, though, nobody was sure what was to come. Being able to work from home at that time, which allowed me to travel and spend a month with my family, was critical to staying optimistic about the present and future. I felt so thankful to be at a company where I was encouraged to be with my family, and where Megan and Sean St. Marie had created a culture of sharing and support.

I was grateful for my role with Modern Memoirs at that time for one other reason: my work was unexpectedly helpful in dealing with the new changes in my life. In the course of my work, I would sometimes come across a line of writing by a client that struck me—maybe the line would be about a recent loss, or connecting with a parent, or just being doubtful about the future—and I’d feel seen and comforted, knowing that someone else at some time had felt the same way.

In that vein, people sometimes wonder why they should publish a memoir as an “average” person with experiences like those of many others. But I see the similarity of our experiences as a benefit, not a drawback. That similarity is what allows us to connect through something as small as a description of a feeling, or a retelling of an event. It is precisely what makes these memoirs so valuable, and what allows a family to feel close to an ancestor simply by reading about their life, never having met them in person.

4. Good work feeds the soul.

With that said, my favorite part of working at Modern Memoirs, by far, is the sense of purpose I had in the knowledge that I helped bring someone’s story into the world. The days that we received advance books from the printer were like a birthday party, with the whole team gathering in the conference room to admire our collective work. I regard the books that I had more of a hand in with particular fondness, and I feel warm when thinking of them being enjoyed by the author’s family. The lovely notes and gifts we often received after completing a project bolstered the sentiment that our work is truly important and valued.

As I say goodbye to Modern Memoirs, I am confident that the company will continue to grow and thrive for years to come. I look forward to keeping in touch to see how the close-knit team I value so much will mentor new interns and publishing associates, forge intimate connections with authors, and bring new stories into the world as distinctive, beautiful books.